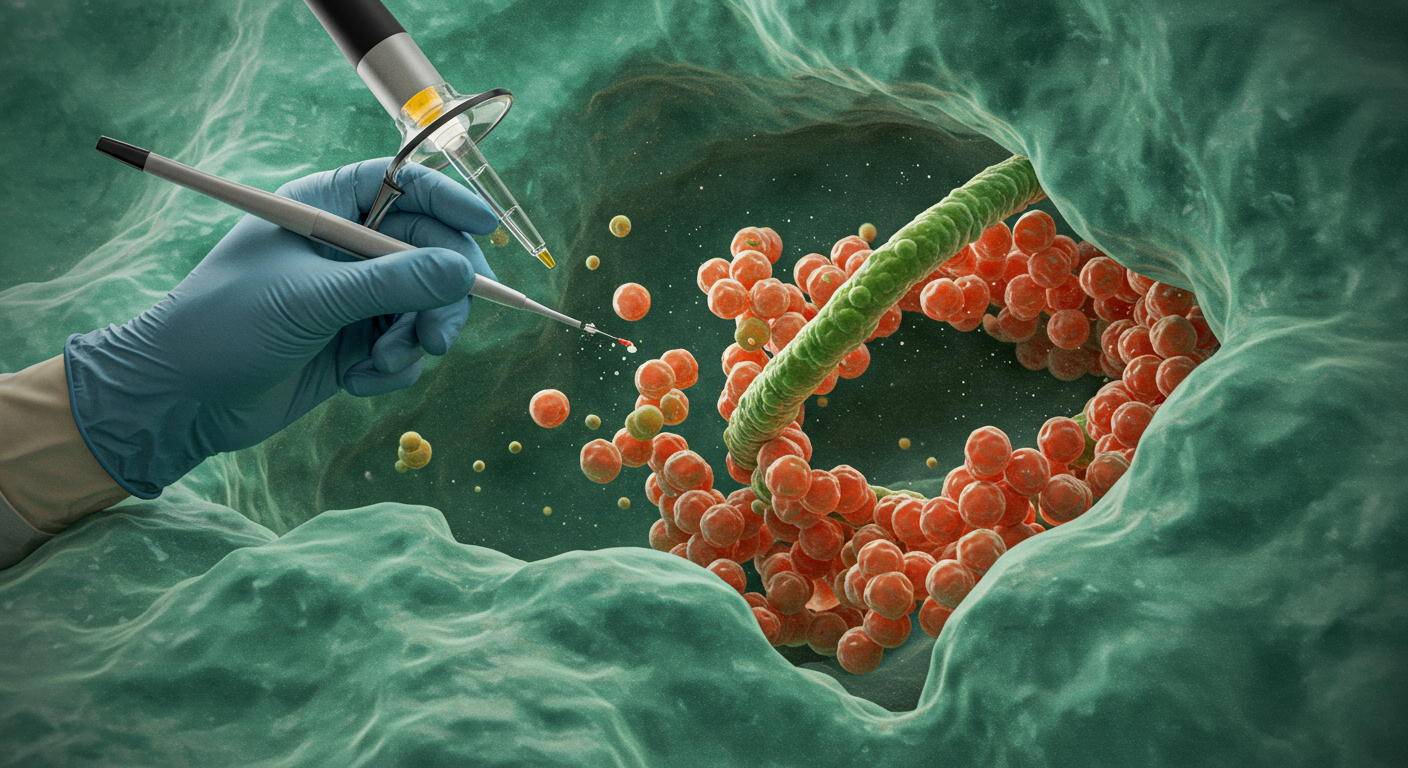

Scientists have uncovered a novel method for controlling the chemical reactions in water-splitting catalysts, a critical step in the production of green hydrogen. By adjusting the operating temperature, researchers can trigger a fundamental shift in the reaction pathway on the surface of a rhodium-ruthenium oxide catalyst. This discovery provides a new layer of control over the process, allowing for a balance between the speed of the reaction and the durability of the catalyst material, a key challenge that has hindered the widespread adoption of this technology.

The finding centers on the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), often the most difficult and energy-intensive part of splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. Catalysts based on ruthenium are known for their high activity but suffer from poor stability, dissolving during the reaction. This new research demonstrates that a specific rhodium-ruthenium oxide catalyst can be coaxed to operate via two different mechanisms. At lower temperatures, it uses a pathway that preserves the catalyst’s structure, while at higher temperatures, it switches to a more aggressive, but highly efficient, mechanism, providing a strategy to optimize the hydrogen production process for industrial scales.

The Challenge of Efficient Water Splitting

The global pursuit of carbon-neutral energy sources has placed immense focus on green hydrogen as a clean fuel and chemical feedstock. Produced through water electrolysis powered by renewable energy, green hydrogen’s primary bottleneck is the OER. This half of the water-splitting equation is notoriously sluggish and requires highly active catalysts to proceed at a meaningful rate. While precious metals like iridium have demonstrated both the activity and stability required, their scarcity and high cost are significant barriers to building the large-scale electrolyzers needed for a hydrogen economy.

Ruthenium-based oxides have long been studied as a more abundant and potentially cheaper alternative. They exhibit excellent initial performance, often outperforming iridium catalysts. However, this high activity comes at the cost of stability. Under the harsh, acidic conditions of a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer, ruthenium catalysts tend to corrode and dissolve. This degradation shortens the lifespan of the electrolyzer and makes the process economically unviable for long-term, continuous operation. The central challenge for scientists has been to design a catalyst system that can provide both high efficiency and the robust durability required for commercial applications.

A Tale of Two Catalytic Pathways

At the heart of the catalyst’s performance and stability are the precise chemical steps that occur on its surface. For ruthenium-based oxides, the OER can proceed through two main routes: the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) and the lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism (LOM). The pathway the reaction takes is determined by the catalyst’s structure and the operating conditions, and it has profound consequences for both the rate of oxygen production and the longevity of the catalyst itself.

The Conventional Route

The adsorbate evolution mechanism is the more conventional pathway for many oxide catalysts. In this process, water molecules react with active metal sites on the surface of the catalyst, forming intermediate oxygen-containing species. These surface-bound intermediates then combine to form an oxygen-oxygen bond, releasing molecular oxygen. Critically, the oxygen atoms that make up the crystal structure of the catalyst itself—the lattice oxygen—do not participate directly in the reaction. This is a significant advantage for stability, as the underlying framework of the catalyst remains intact. While the AEM ensures the catalyst does not consume itself, it often results in a slower reaction rate compared to the alternative pathway.

The High-Activity Route

The lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism offers a more powerful, albeit riskier, alternative. In this pathway, the catalyst’s own lattice oxygen is activated and participates directly in the oxygen evolution reaction. This route can significantly accelerate the process because it bypasses some of the energetic hurdles associated with the AEM, leading to a much higher intrinsic activity. The downside is severe: the participation of the lattice oxygen can lead to the formation of vacancies and structural defects, ultimately causing the ruthenium to dissolve into the electrolyte. This self-oxidation process is the primary reason why many highly active ruthenium catalysts degrade so quickly during operation.

Unveiling the Temperature-Dependent Switch

The breakthrough came when researchers studying a specific binary metal oxide, RhRu3Ox, identified a direct link between the operating temperature and which of the two catalytic pathways was dominant. Using advanced techniques like electrochemical mass spectroscopy, they observed for the first time a Temperature-Dependent Mechanism Transition (TDMT) effect. This finding fundamentally enriches the scientific toolbox for manipulating OER kinetics, moving beyond simple material composition to include operational parameters.

At room temperature, the RhRu3Ox catalyst was found to favor the more stable AEM pathway. The reaction proceeds steadily without significant degradation of the material. However, as the temperature was increased, a distinct switch occurred. The catalyst transitioned to the more aggressive and highly efficient LOM pathway. This transition helps explain why many ruthenium catalysts perform well initially but fail over time, especially as operating temperatures in industrial electrolyzers can fluctuate and rise. The ability to trigger this switch intentionally opens up new possibilities for process control. Operators could potentially run electrolyzers at lower temperatures for stability and ramp up the temperature only when maximum hydrogen production is needed, carefully managing the trade-off between output and catalyst lifespan.

Advanced Analysis and Theoretical Underpinnings

Confirming this mechanism switch required a combination of sophisticated experimental observation and powerful theoretical modeling. Using Density Functional Theory (DFT), scientists were able to probe the energetic landscape of the reaction on the catalyst’s surface. These calculations revealed the existence of a kinetic barrier that prevents the lattice oxygen from being activated at lower temperatures. This barrier is what keeps the catalyst locked into the more stable AEM pathway during operation at or near room temperature.

However, the modeling also showed that this energy barrier could be overcome with the addition of thermal energy. As the temperature rises, there is enough energy in the system to surmount the activation barrier, allowing the more potent LOM pathway to engage. This theoretical insight perfectly matched the experimental evidence, providing a robust explanation for the observed TDMT effect. This synergy between theory and experiment is crucial, as it allows researchers to not only see what is happening but also understand why, paving the way for more targeted and intelligent catalyst design in the future.

Implications for Catalyst Design and Durability

The discovery of the TDMT effect in rhodium-ruthenium oxides has significant implications for the future of green hydrogen production. It suggests that the operational stability of highly active catalysts can be customized and controlled, not just by altering their chemical composition, but by managing the conditions under which they operate. By understanding that temperature acts as a trigger, engineers can design PEM electrolyzer systems that are more efficient and durable.

This new knowledge provides a clear direction for developing next-generation catalysts. The goal is to create materials where the energy barrier to activate the LOM pathway is finely tuned. An ideal catalyst might operate via the stable AEM under standard conditions but allow for the LOM to be engaged in a controlled manner for short bursts of high activity, without causing catastrophic degradation. This approach could lead to catalysts with orders-of-magnitude lifespan extension, making the widespread use of PEM electrolyzers for industrial-scale hydrogen production a more achievable reality. Ultimately, this research transforms temperature from a simple variable into a sophisticated tool for dictating the chemical route a reaction takes.