New observations from the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft are challenging long-held theories about our sun’s magnetic activity. For the first time, scientists have directly witnessed the movement of the sun’s magnetic field at its south pole, revealing a surprisingly rapid migration that could reshape our understanding of the solar cycle and its effects on space weather. These groundbreaking findings provide a crucial piece of the puzzle in comprehending the inner workings of our star.

The data, collected in March 2025, shows that the magnetic structures are drifting towards the pole at speeds of 10 to 20 meters per second, a rate comparable to what is observed at the sun’s lower latitudes. This contradicts previous models which suggested that this “magnetic conveyor belt” should slow down significantly near the poles. By providing the first direct measurements of this polar flow, the Solar Orbiter is offering a fresh perspective on the 11-year cycle that governs solar flares and coronal mass ejections, events that can have significant impacts on Earth’s technological infrastructure.

A New Vantage Point in Solar Science

For decades, a complete understanding of the sun’s global magnetic field has been hampered by a critical blind spot: its poles. From Earth’s perspective, we can only ever get a glancing, oblique view of these regions. Most spacecraft that have studied the sun have done so from the ecliptic plane, the flat plane in which the planets orbit, leaving the polar areas largely unexplored. This has forced scientists to rely on inferences and models to fill in the gaps in their knowledge of the polar magnetic dynamics, which are crucial drivers of the sun’s overall magnetic cycle.

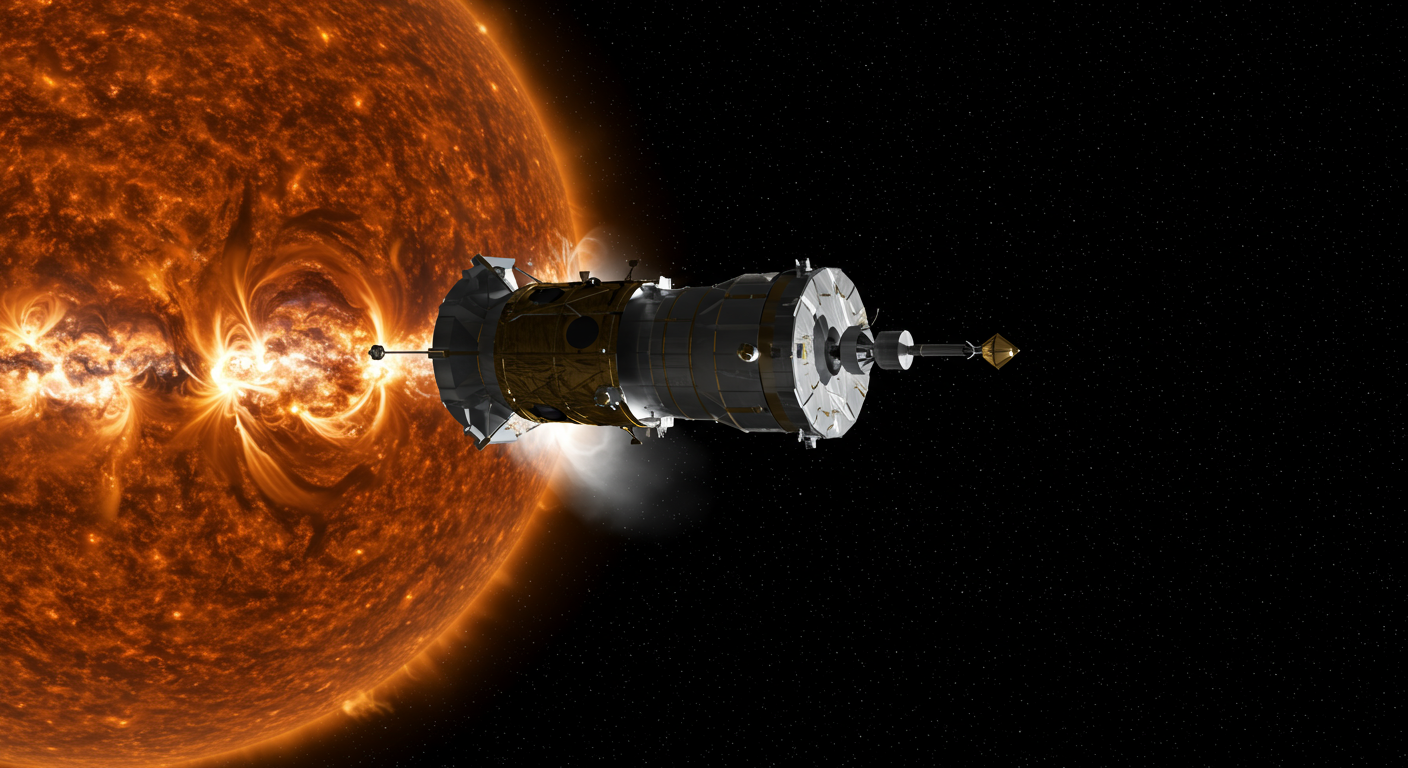

The Solar Orbiter mission, a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA, was designed specifically to address this observational challenge. Launched in 2020, the spacecraft is on a unique trajectory that will take it out of the ecliptic plane, allowing it to fly over the sun’s poles and capture the first-ever direct images of these enigmatic regions. In March 2025, the orbiter tilted its orbit by 17 degrees, providing an unprecedented view over the sun’s southern limb and enabling the collection of the data that has led to these new discoveries. This new perspective is essential, as the polar regions are where the sun’s large-scale magnetic field is shaped and ultimately reverses every 11 years.

Tracing the Sun’s Magnetic Network

To map the movement of the magnetic field, scientists needed to find a way to make the invisible visible. They did this by tracking the movement of gigantic plasma cells on the sun’s surface known as supergranules. These are vast areas of churning, hot plasma, each two to three times the diameter of Earth, that cover the sun’s surface. The horizontal flow of plasma within these supergranules sweeps magnetic field lines to their edges, creating a constantly shifting, web-like pattern of strong magnetic fields across the sun. This “magnetic network” is a key component of the sun’s surface magnetism.

Imaging with Ultraviolet Light

The research team, led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, used data from two of the Solar Orbiter’s instruments: the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI). The magnetic network on the solar surface leaves an imprint in the chromosphere, the layer of the sun’s atmosphere just above the surface. In images taken by the EUI, these imprints show up as bright spots. Over a period of eight days, from March 16 to 24, 2025, the spacecraft continuously observed the south pole. By compiling these images, the scientists were able to create a composite view that showed the tracks of these bright spots. Influenced by the sun’s rotation, these tracks appeared as long, bright arcs, clearly indicating the direction and speed of the underlying magnetic flow.

A Surprising Velocity

The analysis of these bright spot tracks delivered a significant surprise. The researchers measured the poleward drift of the magnetic field to be between 10 and 20 meters per second, or about 22 to 45 miles per hour. While this may seem slow in terrestrial terms, it is remarkably fast for the sun’s polar regions. Previous models, based on observations from lower latitudes, had predicted that this flow, a key part of the sun’s “magnetic conveyor belt,” would become much slower as it approached the poles. The new data shows that the flow maintains a significant speed, nearly as fast as the flows closer to the equator. This was the first time this polar magnetic transport had been directly mapped from above the solar limb, providing a concrete measurement that challenges decades of theoretical work.

Implications for the Solar Cycle

This unexpectedly rapid polar flow has profound implications for our understanding of the sun’s 11-year magnetic cycle. This cycle is driven by a process known as the solar dynamo, which involves a “magnetic conveyor belt” of plasma currents. On the surface, these currents carry magnetic field lines from the equator towards the poles. Deep inside the sun, a return flow carries them back towards the equator. This global circulation is what sustains the sun’s magnetic field and dictates the rhythm of its activity, from the appearance of sunspots to the eruption of powerful solar storms.

The new, faster speed measurement for the surface part of this conveyor belt could change our models of the entire system. A faster flow of magnetic flux to the poles might affect the timing of the solar cycle, potentially shortening the period between solar maxima, the peaks of solar activity. It could also influence the strength of the subsequent cycle. As Sami Solanki, a director at the Max Planck Institute and a co-author of the study, noted, understanding what happens at the sun’s poles has been the missing piece of the puzzle for comprehending the sun’s magnetic cycle. The Solar Orbiter is now beginning to provide that missing piece.

The Future of Polar Exploration

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, represent a significant milestone, but they are based on a relatively short period of observation. This initial glimpse has provided a snapshot of the polar dynamics, but further observations are needed to determine if this rapid flow is a constant feature or if it varies over the course of the solar cycle. The Solar Orbiter mission is planned to last for many years, and as it continues its journey, it will gradually increase its orbital inclination, eventually reaching an angle of 33 degrees. This will provide even more direct and detailed views of the sun’s polar regions.

These future observations will be crucial for refining the models of the solar dynamo and improving our ability to forecast space weather. By getting a complete picture of the sun’s global circulation, scientists hope to better predict the timing and intensity of solar cycles, which can have far-reaching consequences for our technologically dependent society. The Solar Orbiter’s ongoing exploration of the sun’s poles promises to continue to reveal new insights into the behavior of our nearest star.