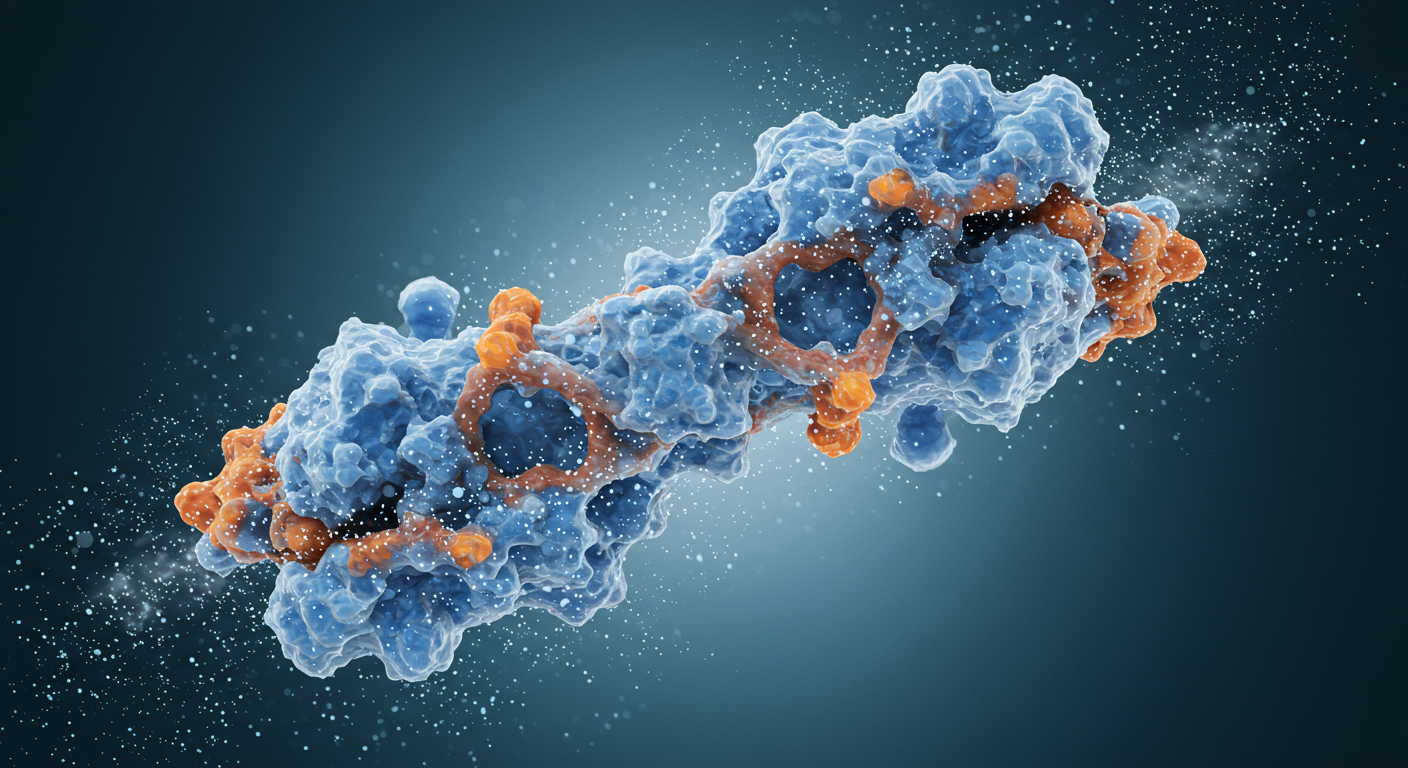

Chemists have successfully reimagined the role of deoxyribonucleic acid, demonstrating for the first time that its fundamental phosphate backbone can serve as a powerful and precise catalyst for creating specific mirror-image molecules. The breakthrough, led by researchers at the National University of Singapore, harnesses the inherent chirality of the DNA double helix to guide chemical reactions, a method that promises to make the production of advanced pharmaceuticals more efficient and environmentally friendly. This discovery leverages a natural bio-molecular structure to solve a complex challenge in synthetic chemistry, opening a new frontier in biocatalysis.

The work addresses a critical obstacle in drug development known as asymmetric catalysis, the process of selectively producing one of two possible mirror-image forms of a molecule. Many modern drugs are chiral, meaning they exist in “left-handed” and “right-handed” versions that can have vastly different effects on the body; one may be a potent therapeutic while its counterpart is inactive or even dangerous. Traditional methods for producing a single, desired version often rely on complex procedures and organic solvents. By using DNA’s phosphate groups to control reactions in water, the new technique offers a more sustainable and direct pathway to manufacturing high-value, structurally complex compounds with the correct geometric orientation.

The Molecular Mirror-Image Problem

In the world of chemistry, many molecules are chiral, a property describing a structure that cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, much like a person’s left and right hands. These two forms, called enantiomers, have identical chemical formulas but a different three-dimensional arrangement of atoms. While they share most physical properties, they often interact very differently with other chiral molecules, such as the receptors and enzymes found in the human body. This distinction is profoundly important in medicine and pharmacology, where the biological activity of a drug is dictated by its specific shape.

Producing only the therapeutically active enantiomer is a central goal of pharmaceutical manufacturing. The history of medicine includes cautionary tales where the wrong enantiomer led to severe side effects, making stereoselectivity a paramount concern for safety and efficacy. The field of asymmetric synthesis is dedicated to developing catalysts that can steer a chemical reaction to yield one mirror-image form over the other. These catalysts are themselves chiral and act as templates, influencing the orientation of reactants to build the desired molecular structure. However, developing effective catalysts can be a difficult and expensive process, driving a continuous search for novel and more efficient approaches.

Harnessing a Biological Blueprint

The research team, guided by Assistant Professor ZHU Ru-Yi at the Department of Chemistry, drew inspiration from a fundamental process in biology: the interaction between DNA and proteins. In living cells, the negatively charged phosphate groups that form the backbone of the DNA molecule create natural attraction points for positively charged amino acid residues on proteins. This electrostatic interaction is essential for countless biological functions, including DNA replication and gene regulation. The researchers theorized that this well-understood biological principle could be repurposed for synthetic chemistry.

Their central hypothesis was that the DNA backbone could function as an intrinsically chiral scaffold. If positively charged reactants were brought near it, the phosphate groups could attract and temporarily hold them in a fixed orientation dictated by the DNA’s helical structure. This precise positioning, they believed, would force the subsequent reaction to proceed in a highly controlled manner, yielding a single, predictable enantiomer as the final product. This approach effectively co-opts the genetic molecule itself not for its code, but for its physical and electrical properties, turning it into a programmable tool for chemists.

A Mechanism Based on Ion-Pairing

Guiding Reactions in Water

The new catalytic method operates on a principle known as asymmetric ion-pairing catalysis. In this process, the DNA phosphates form a temporary, non-covalent bond with cationic (positively charged) reagents. This “ion-pairing” effect is the key to the catalyst’s effectiveness. The DNA molecule acts like a tiny magnet with a specific shape, attracting the reactant and holding it in just the right position for the reaction to occur with the desired stereochemical outcome.

A significant advantage of this system is its ability to function effectively in water. Many conventional organocatalytic methods require non-polar or weakly polar organic solvents to work, as the polar nature of water can interfere with the subtle interactions needed for catalysis. By contrast, the strong electrostatic attraction between the DNA phosphates and cationic reagents is robust enough to operate in an aqueous environment. This not only mimics biological processes more closely but also represents a major step forward in green chemistry, reducing the reliance on potentially hazardous and environmentally harmful solvents. The team successfully demonstrated this effect across four different types of chemical transformations, including fluorination and Mannich reactions, proving its versatility.

Pinpointing the Catalytic Sites

To confirm that the phosphate groups were indeed the primary drivers of the catalytic activity, the researchers developed an innovative experimental technique they named “PS scanning.” This method involved systematically replacing individual phosphate groups along the DNA strand with closely related chemical look-alikes that lacked the same charge properties. By running the reactions with these modified DNA strands, they could observe how the catalytic efficiency and stereoselectivity changed. The results allowed them to map which specific phosphates were most critical for guiding the reaction, providing conclusive evidence for the proposed mechanism and offering deeper insight into the catalyst’s dynamic and adaptive nature.

Advancing Sustainable Drug Production

The findings represent what Assistant Professor Zhu calls a “conceptual breakthrough” in biocatalysis. The research expands the toolkit of synthetic chemists and provides a powerful platform for developing more sustainable manufacturing processes, particularly for complex molecules that are expensive and difficult to produce. By using DNA, an abundant and biocompatible polymer, as the catalyst, this method avoids the need for rare metals or intricate synthetic catalysts that are often required for asymmetric reactions. The ability to tailor the DNA sequence also offers a high degree of customizability, suggesting that catalysts could be designed for highly specific chemical transformations in the future.

Looking ahead, the NUS team plans to expand on this work by exploring more ways to use DNA phosphates to create a wider array of chiral compounds essential for drug discovery and development. The success of this DNA-based system opens the door for using other biological macromolecules as scaffolds for catalysis. This research blurs the line between biology and synthetic chemistry, harnessing the elegant solutions perfected by nature to solve modern manufacturing challenges and build the complex, high-value molecules of the future.