The vast and complex nervous system within the gastrointestinal tract, often called the body’s “second brain,” possesses a remarkable defense mechanism previously unknown to science. New research reveals that gut neurons, faced with threats from pathogenic bacteria and parasites, can develop a form of tolerance. A prior infection, despite causing initial damage, appears to prime the system, shielding these critical neurons from being destroyed during future encounters with dangerous microbes.

This discovery challenges the conventional understanding of infections, which are typically viewed as purely damaging events. A study demonstrates that an initial bout of a foodborne illness can trigger a protective state in the gut’s enteric nervous system, preventing the large-scale neuronal death that can lead to chronic gastrointestinal diseases. This finding opens up new avenues for understanding and potentially treating conditions like post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), suggesting that the long-term health of the gut may be shaped by a history of its battles with pathogens.

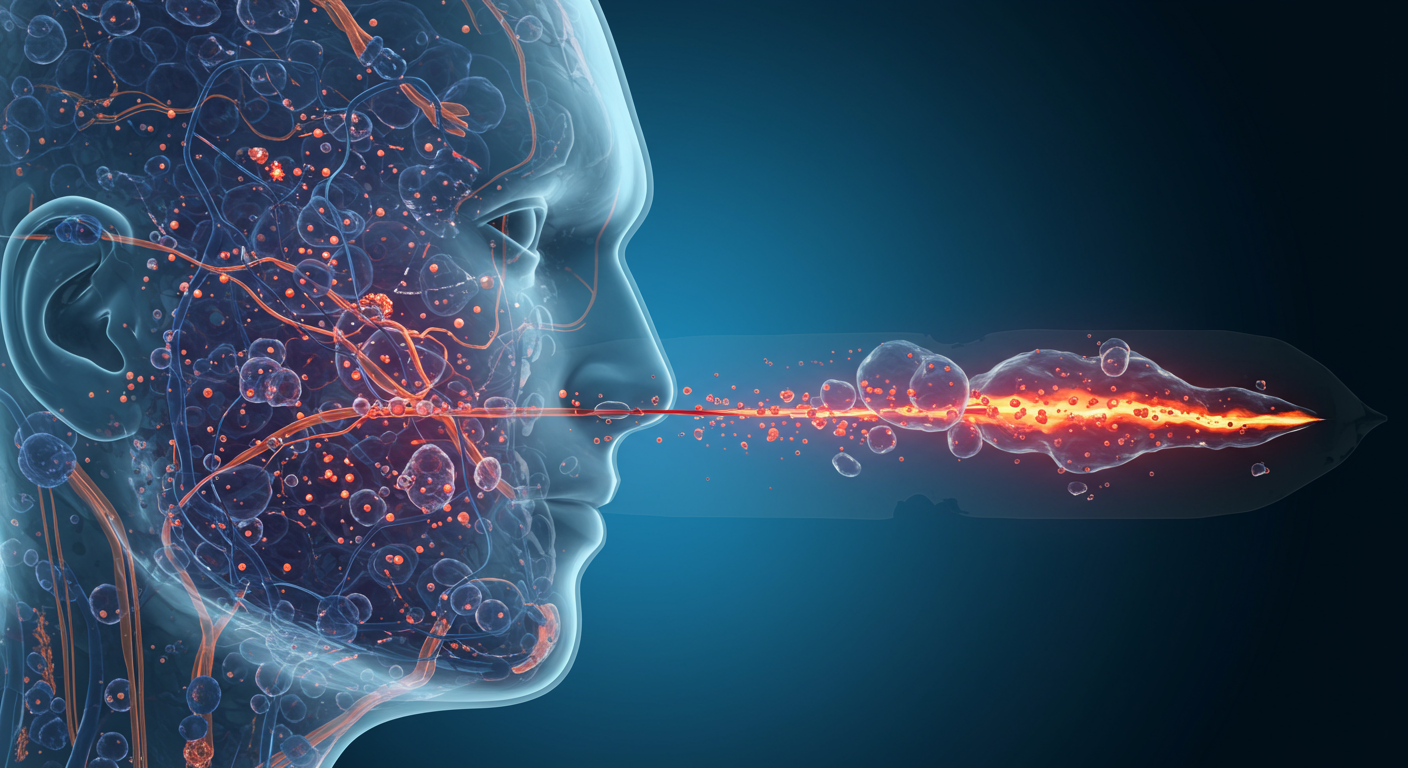

The Gut’s Autonomous Brain

Deep within the walls of the gastrointestinal tract lies the enteric nervous system (ENS), a sprawling network of approximately 100 million neurons. This system is so extensive and capable of operating with such significant autonomy that scientists have nicknamed it the “second brain.” It manages the complex processes of digestion, including the churning of intestinal contents, the secretion of enzymes, and the coordination of local blood flow, largely without input from the central nervous system. The ENS is organized into two primary layers of ganglia: the myenteric plexus, which controls muscle movement, and the submucosal plexus, which regulates secretions and blood flow.

This intrinsic nervous system uses more than 30 neurotransmitters, many of which are identical to those found in the brain, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin. In fact, the gut produces over 90% of the body’s serotonin, highlighting its crucial role in not just digestion but also overall well-being. The ENS acts as a critical interface, sensing the luminal environment and orchestrating responses to everything from nutrients to hostile invaders. When pathogens breach the gut’s defenses, these neurons are on the front lines, directly in the path of potential harm.

Neuronal Casualties of Infection

An infection from foodborne pathogens like Salmonella or from parasites can have devastating consequences for the enteric nervous system. The toxins released by certain bacteria, such as Clostridioides difficile, can directly stimulate enteric neurons, leading to the diarrhea and inflammation characteristic of a gut infection. More alarmingly, research has shown that these infections can lead to a significant and lasting loss of enteric neurons. When enough of these neurons die off, the intricate control of gut motility and function can spiral out of control, leading to long-term health problems.

This neuronal loss is a suspected culprit behind post-infectious functional gastrointestinal disorders. The symptoms of conditions like IBS—which include chronic constipation, diarrhea, and pain—closely mirror the expected consequences of a damaged enteric nervous system. This has led researchers to hypothesize that minor gut infections might cause more significant neuronal die-offs in some individuals than in others, predisposing them to these chronic conditions. The question for scientists was whether the body had any natural defense mechanism to protect its second brain from this kind of catastrophic damage.

A Protective Tolerance Emerges

Evidence from Bacterial Challenges

To investigate how the gut protects its neurons, researchers conducted experiments using a non-lethal strain of Salmonella in mice. The initial infection caused the mice to lose a number of their enteric neurons as they fought off and cleared the bacteria over the course of about a week. However, when these same mice were later exposed to a second, similar foodborne bacterium, the results were strikingly different. The mice suffered no additional loss of enteric neurons, indicating that the first infection had activated a powerful protective tolerance.

Parasites Elicit a Similar Defense

The team then explored whether this protective effect was unique to bacterial infections or if it extended to other types of pathogens. They infected a different group of mice with a common parasitic helminth. This infection also proved to protect the enteric neurons from damage during a subsequent bacterial infection. The discovery that both bacteria and parasites could induce this neuroprotective state, despite triggering different immune pathways, suggested the existence of a robust and fundamental defense mechanism. This was further supported by examining mice from a pet store, which, having been exposed to a variety of microbes, already possessed this tolerance and suffered no neuronal loss when infected in the lab.

The Role of Macrophages in Neuroprotection

The key to this neuronal shield appears to be the gut’s resident immune cells, specifically muscularis macrophages. Previous work had already established that these macrophages can produce specialized molecules that prevent neurons from dying in response to stress. The new study connected this function directly to infections. The researchers hypothesized that a primary infection activates these macrophages, which then adopt a neuroprotective posture, ready to defend the neurons against future threats. This pathway represents a unique form of immunological memory that is not about clearing pathogens more quickly but about mitigating the collateral damage of an infection.

By activating this macrophage-driven defense, the enteric nervous system becomes more resilient. The body essentially learns from the first pathogenic encounter, not just how to fight the microbe, but how to protect its own critical infrastructure. This mechanism ensures that even if the body is repeatedly exposed to pathogens, the integrity of its “second brain” is preserved, preventing the cumulative damage that could otherwise lead to severe, chronic disease.

Implications for Human Gastrointestinal Health

The discovery of this protective mechanism has profound implications for understanding and treating human gastrointestinal disorders. It provides a potential explanation for why some individuals develop post-infectious IBS while others recover fully. It is possible that those who develop chronic conditions have an impaired ability to activate this neuroprotective macrophage response, leading to greater neuronal loss during an infection.

This insight could pave the way for new therapeutic strategies. Rather than focusing solely on eliminating a pathogen or managing symptoms, future treatments could aim to bolster this natural defense system. Therapies might be developed to “pre-train” the gut’s macrophages to protect neurons, effectively inoculating the enteric nervous system against the damage of future infections. Such an approach could be transformative for preventing the transition from an acute gut infection to a lifelong chronic illness, offering hope to millions who suffer from unexplained gastrointestinal problems.