A consortium of researchers in Germany has developed a new, high-performance bioplastic derived from a byproduct of the paper and pulp industry. The material, a novel type of polyamide, not only comes from a renewable source but also exhibits superior functional properties compared to traditional petroleum-based plastics, potentially offering a sustainable alternative for a wide range of demanding applications in medicine, engineering, and textiles.

The new material, named Caramide, is synthesized from 3-carene, a chemical compound found in turpentine, which is a waste product from cellulose production. Developed by a team across six Fraunhofer institutes, this bio-based plastic can be engineered to have specific properties, making it adaptable for uses from lightweight automotive parts to surgical sutures. The project aims to accelerate the creation of such materials, moving beyond sustainability as a sole objective to creating bio-based products that outperform their fossil-fuel counterparts.

A Novel Bio-Based Polyamide

The new plastic belongs to a class of materials called polyamides, which are known as high-performance thermoplastics. Caramide represents a significant advancement in this category because it is completely bio-based. Polyamides are characterized by their strength, durability, and resistance to heat and chemicals, making them common in everything from car engines to clothing fibers. The research team has demonstrated that Caramide not only matches these qualities but can exceed them.

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB first developed the foundational monomers for Caramide about a decade ago. The current project, called SUBI²MA, has brought together the expertise of multiple institutes to refine the material and its production processes. The result is a plastic that leverages its biological origins to provide functional advantages over plastics derived from petroleum.

From Forest Byproduct to Advanced Polymer

The Source Material

Caramide is derived from 3-carene, a natural organic compound classified as a terpene. Terpenes are abundant in nature and are primary components of essential oils and plant resins. The specific source of 3-carene used for this process is a byproduct of cellulose production, an industry that generates large quantities of terpene-rich waste streams. This approach adds value to what is often considered industrial residue, creating a more circular and sustainable manufacturing chain.

Synthesis Process

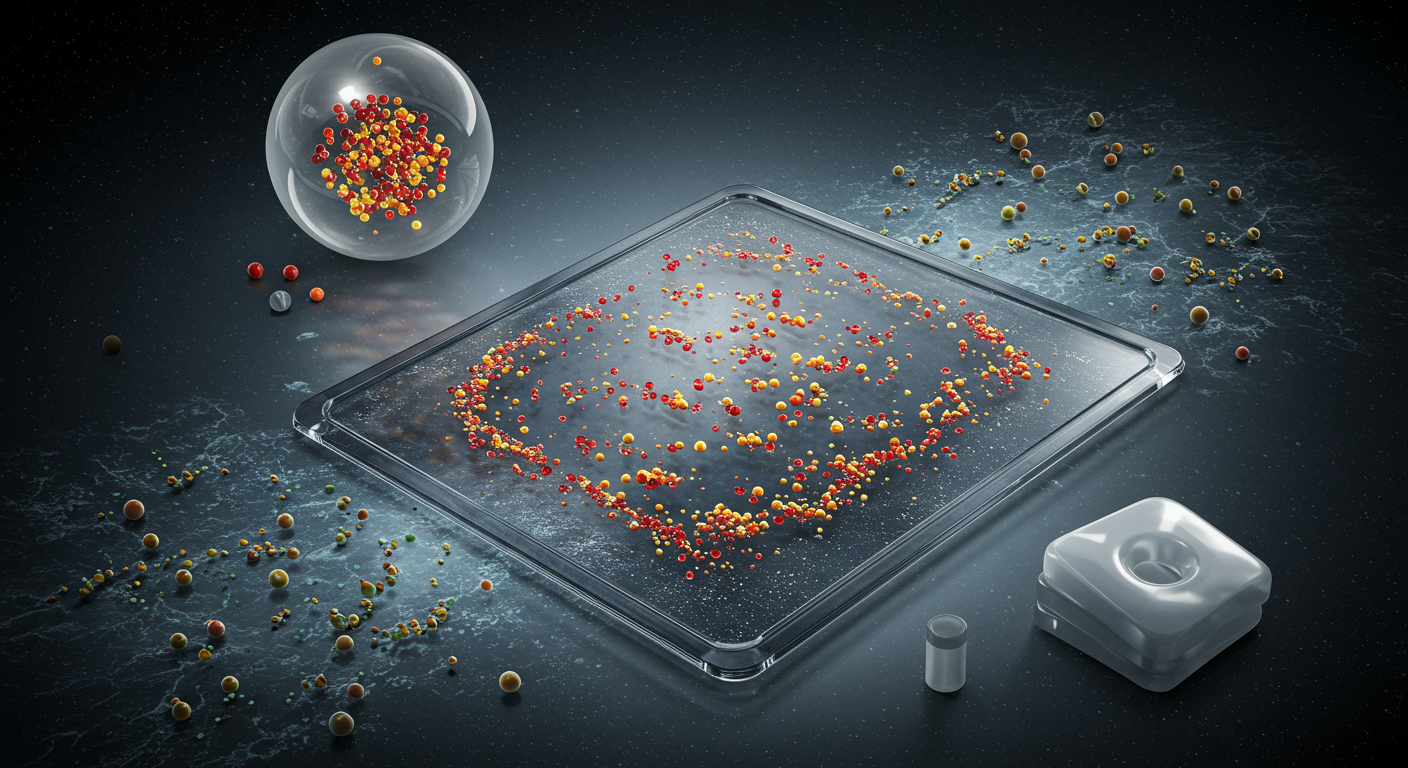

Scientists at Fraunhofer’s Straubing branch developed a method to convert 3-carene into monomers, the molecular building blocks of polymers. These monomers, specifically 3S-caranlactam and 3R-caranlactam, are then polymerized to create Caramide. This process of creating polymers from biological starting materials is a key focus of green chemistry and materials science, aiming to reduce reliance on finite fossil fuels. The project’s success demonstrates a viable pathway for producing high-value materials from renewable feedstocks.

Chirality and Tunable Properties

One of the most significant features of Caramide is its chirality, a molecular property where two molecules are mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed, much like a person’s left and right hands. This structural characteristic, stemming from its natural source material, has a direct impact on the plastic’s physical, chemical, and biological functions. It allows researchers to fine-tune the material’s properties with a high degree of precision.

During the research, the team discovered that the two different caranlactam monomers lead to Caramides with distinct properties. By controlling which monomer is used, or in what combination, scientists can adjust the final plastic’s characteristics. This adaptability is particularly valuable for specialized fields like medical technology or advanced sensors, where materials must meet very specific performance criteria. The chirality provides a functional advantage that is not typically found in conventional fossil-based polyamides.

Versatile and High-Performance Applications

The unique thermal properties and adaptability of Caramide make it a promising candidate for a diverse array of applications. Its resistance to high temperatures is a key feature, opening up uses in demanding environments. So far, researchers have successfully manufactured several items from the new polyamide, including monofilaments, foams, and transparent plastic glasses.

Potential uses span multiple industries. In mechanical engineering, it could be used for durable gears and components. Its properties make it suitable for safety glass and lightweight construction panels in the automotive or aerospace sectors. In the medical field, it could be used for advanced protective textiles or as a material for surgical sutures. The ability to tailor the material at a molecular level means it can be optimized for specific functions, from resisting mechanical stress to having particular interactions with biological tissues.

A Collaborative Path to Sustainable Materials

The development of Caramide is part of a larger German research initiative named the SUBI²MA flagship project. This collaborative effort involves six separate Fraunhofer institutes, combining their expertise in materials science, biotechnology, and process engineering. The project has three primary goals: advancing new bio-based materials like Caramide, developing novel biohybrid materials that incorporate functional biomolecules, and creating a “digital fast-track” to accelerate future material development.

Beyond creating a single new plastic, the project aims to establish a methodology for designing and producing sustainable materials more efficiently. This includes the creation of biohybrid materials, where functional molecules like enzymes or bio-based flame retardants are integrated into plastics. These additives could, for example, accelerate the breakdown of conventional plastics like PET or give materials entirely new capabilities, such as built-in biosensors. This broader vision underscores a shift in materials science toward not just replacing old materials, but designing new ones that are fundamentally better in both performance and environmental impact.