A new method that uses the building blocks of proteins to modify ice can trap methane gas in a solid, stable form in mere minutes, a dramatic acceleration that could transform the storage and transportation of natural gas. Researchers have developed an “amino-acid-modified ice” that captures methane with a 30-fold increase in storage capacity and a 29-fold enhancement in reaction speed compared to using pure ice, solving a key bottleneck that has long hindered the use of solidified natural gas technology.

The discovery, led by a team at the National University of Singapore, offers a safer, more energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly alternative to current natural gas storage methods, which involve either high-pressure compression or cryogenic liquefaction at -162°C. While locking methane into an ice-like cage, known as a clathrate hydrate, has been a promising concept, the process was traditionally far too slow for practical, large-scale application. By adding small, biodegradable amino acids, scientists have created a system where 90% of the gas storage capacity is reached in just over two minutes, making the solidified natural gas approach commercially viable for the first time.

A New Recipe for Methane Hydrates

The breakthrough comes from a team of researchers led by Professor Praveen Linga in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the National University of Singapore’s College of Design and Engineering. Their findings, detailed in the journal Nature Communications, present a simple yet powerful workaround to the slow kinetics of hydrate formation. The process begins by dissolving a small quantity of an amino acid into water, which is then frozen to form bulk ice. This ice is subsequently ground into a fine powder, creating what the team calls amino acid-modified ice, or AM-Ice.

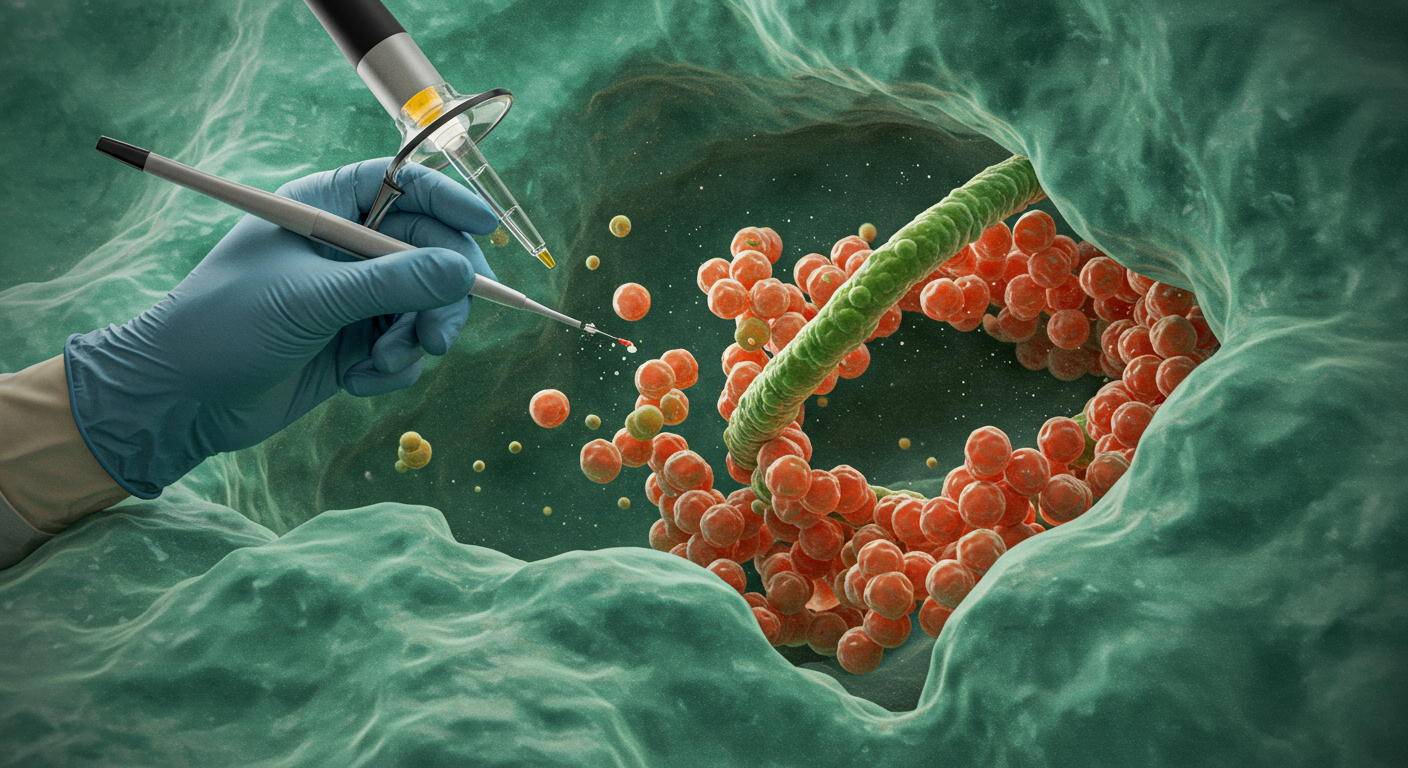

When this powder is exposed to methane under specific, relatively mild conditions—a temperature of 272.7 K (-0.45°C) and a pressure of 6 MPa—it rapidly transforms into a white, expanded solid. This visual change signals the successful formation of a methane hydrate, a crystalline structure where water molecules form a cage-like lattice that physically traps methane molecules inside. The research team systematically tested various parameters, including different amino acids, concentrations, temperatures, and pressures to identify the optimal conditions for the reaction. Their results showed that the amino acid tryptophan at a concentration of 3000 ppm yielded the best performance, achieving a methane storage volume of 146.56 times the volume of the ice itself.

The Mechanism Behind Rapid Gas Capture

The key to the accelerated process lies in how amino acids alter the physical properties of the ice surface. The researchers found that certain amino acids, especially those that are hydrophobic (water-repelling) like tryptophan, facilitate the formation of microscopic liquid layers on the surface of the ice powder as methane gas is introduced. These transient layers serve as ideal nucleation sites, or fertile ground, for hydrate crystals to begin growing. This rapid crystal growth produces a porous, almost sponge-like solid structure that dramatically increases the surface area available for the reaction, allowing methane to be captured much more quickly than in conventional systems.

Molecular-Level Observations

To understand the process at a molecular level, the team employed in-situ Raman spectroscopy. This technique allowed them to observe the real-time occupation of methane molecules within the hydrate’s unique cage structures. Methane hydrates form a structure known as sI clathrate, which contains two different types of cages: a smaller pentagonal dodecahedron (written as 5¹²) and a larger tetrakaidecahedron (5¹²6²). The spectroscopic analysis confirmed the time-dependent filling of both cage types, providing direct evidence of the rapid and efficient trapping mechanism at the most fundamental level. This detailed view confirmed that the amino acids do not simply speed up the reaction but ensure a robust and complete formation of the desired gas-filled hydrate structure.

A Sustainable and Reusable Storage System

Beyond its remarkable speed and capacity, the amino acid method offers significant environmental and practical advantages. The amino acids used are naturally occurring and completely biodegradable, presenting a stark contrast to the synthetic surfactants and polymers sometimes used to promote hydrate formation, which can carry environmental risks. This makes the AM-Ice technology an inherently cleaner approach to gas storage.

Furthermore, the system operates as a closed-loop, reusable cycle. Once the methane is stored, it remains locked in the solid hydrate until needed. Releasing the gas is straightforward and requires only gentle heating. This process effectively mitigates the foaming issues that can plague systems using traditional surfactants. After the methane is recovered, the resulting water-amino acid solution can be simply refrozen and reused to capture more gas, enhancing the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of the entire storage cycle. This combination of performance and green credentials makes the technology highly attractive for a wide range of applications.

Broadening the Horizon for Gas Storage

The immediate application for this technology is in the storage of natural gas, particularly for ensuring a stable energy supply and enhancing global energy resilience. Its efficiency and sustainability are well-suited for both large-scale industrial storage and for capturing and storing biomethane, a renewable natural gas produced from organic waste. By making solidified natural gas a practical reality, this method could help accelerate the transition away from higher-carbon fuels in line with global climate commitments.

The research team sees potential for the technology to extend far beyond methane. They are actively exploring adapting the amino-acid-modified ice technique to store other crucial industrial gases. The primary candidates for future work include hydrogen, a key component of the clean energy economy, and carbon dioxide, for which new capture and sequestration technologies are urgently needed. The successful application of this method to other gases could provide a versatile platform for safer and more efficient management of a wide variety of energy and industrial resources.