Researchers have identified a powerful mechanism that allows melanoma to overcome immunotherapy, the practice of using a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer. A study from UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center reveals that the deadliest form of skin cancer often develops resistance by making large-scale changes to its DNA, altering entire sections of its genetic code. These modifications, known as copy-number variants, involve the deletion or amplification of DNA segments that regulate a cancer cell’s ability to self-destruct.

The discovery, published in the journal Immunity, helps explain a significant challenge in oncology: why many melanoma patients who initially respond well to treatment eventually see their tumors return. While immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized melanoma care, between 40% and 60% of patients experience a relapse as the cancer adapts. By pinpointing how these large genetic alterations allow tumor cells to survive an immune assault, the findings present a new strategy for treatment. Researchers suggest that making cancer cells more susceptible to this programmed cell death could prevent or even reverse resistance, potentially extending the effectiveness of immunotherapy for thousands of patients.

A Deeper Look at a Stubborn Problem

For years, a primary focus of cancer research has been on small-scale point mutations, where single letters of the genetic code are altered. While these changes are important, the UCLA study illuminates the critical role of larger, more sweeping genetic events in the development of treatment resistance. This work shows how relapsing melanoma tumors frequently carry these significant copy-number variations. Instead of a minor spelling error in the genetic instructions, the cancer is tearing out or duplicating entire pages.

This process gives the cancer a formidable advantage. According to Dr. Roger Lo, the study’s senior author and a professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, these large-scale mutations can be a highly efficient way for cancers to evolve. By altering a whole segment of DNA, a tumor can modify the function of multiple genes simultaneously, creating a robust defense against the body’s immune system far more quickly than it could by accumulating individual point mutations.

The Mechanics of Cancer’s Survival

Disarming Self-Destruction Pathways

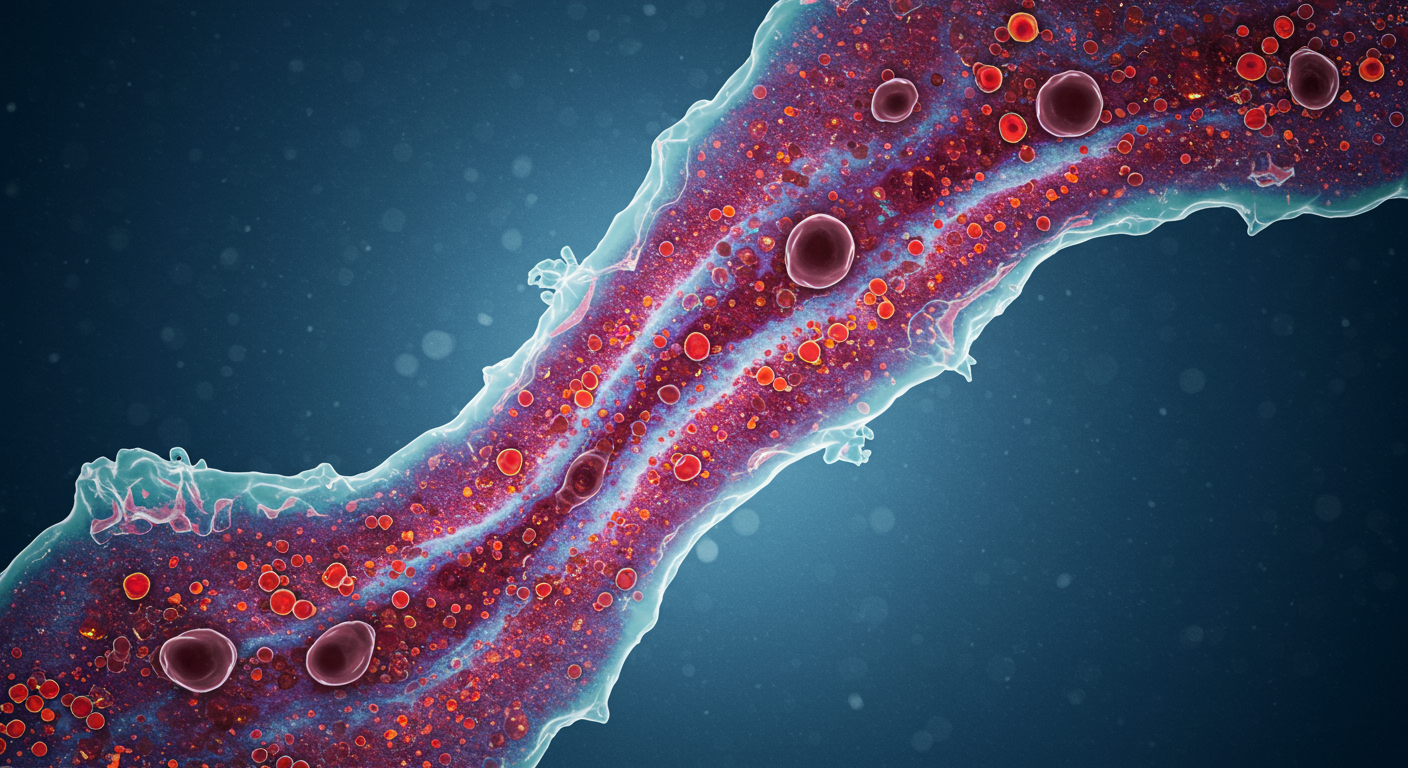

Immune checkpoint inhibitors work by releasing the brakes on the immune system, allowing T-cells to recognize and attack cancerous cells. When this therapy is effective, the immune attack inflicts damage on the tumor cells, which should trigger a process called apoptosis, or programmed cell death. This is a natural, self-scuttling mechanism that eliminates damaged or dangerous cells before they can cause more harm. The study found that melanoma’s copy-number changes directly interfere with this crucial safety measure.

The deleted or amplified DNA sections frequently contain genes that are essential for regulating apoptosis. By shedding genes that promote cell death or amplifying genes that inhibit it, the cancer cells effectively disable their own self-destruct sequence. This cumulative gene dosage imbalance reshapes the tumor’s biology, allowing it to withstand the immune system’s assault. Even when T-cells successfully attack, the cancer cells survive the damage, leading to the eventual regrowth of the tumor months or even years after a patient first went into remission.

Tracing the Seeds of Resistance

Resistance Before Treatment Begins

One of the more striking findings from the research is that the seeds of resistance may be planted long before a patient receives their first dose of immunotherapy. Using advanced single-cell whole-genome sequencing, the investigators analyzed tumor samples from patients taken both before and after treatment. They discovered that in some cases, small subsets of tumor cells already possessed these resistance-driving genetic changes prior to the start of therapy.

Natural Selection in Tumors

This pre-existing variation provides fuel for natural selection once treatment begins. The immunotherapy drugs successfully eliminate the susceptible cancer cells, but the small population of pre-resistant cells can survive and multiply, eventually becoming the dominant clone in the relapsed tumor. This insight suggests that for some patients, a passive “wait-and-see” approach during remission might not be the best strategy, as it allows these resistant subclones the time to grow. The relapsed tumors were also found to be highly diverse, containing multiple subclones with distinct DNA copy-number variations, further complicating future treatment efforts.

New Pathways to Overcome Resistance

Restoring Vulnerability in the Lab

Building on their discovery, the researchers tested a potential counter-strategy. The findings strongly suggested that if the cancer’s resistance is based on avoiding programmed cell death, then forcing the issue could restore the effectiveness of immunotherapy. They conducted experiments in both laboratory cell lines and mouse models to test this hypothesis.

In these experimental models, sensitizing the melanoma tumors to apoptosis showed highly promising results. By making the cancer cells more prone to self-destruct, the researchers were able to enhance the effects of the immune attack triggered by checkpoint inhibitors. This proof of concept provides a strong foundation for developing new drugs or combination therapies that could be used alongside existing immunotherapies to produce a more durable response and prevent the cancer from escaping.

Future Clinical Directions

The immediate goal for the research team is to expand its analysis to include more patients and a wider array of experimental models to validate the findings further. The ultimate aim is to translate this knowledge into a clinical trial designed specifically to lower the rate of relapse in melanoma patients. Such a trial would likely test the combination of standard immune checkpoint inhibitors with a new agent that promotes apoptosis in cancer cells. This research adds a critical new dimension to the understanding of how cancers adapt and could pave the way for a new generation of more effective and longer-lasting treatments.