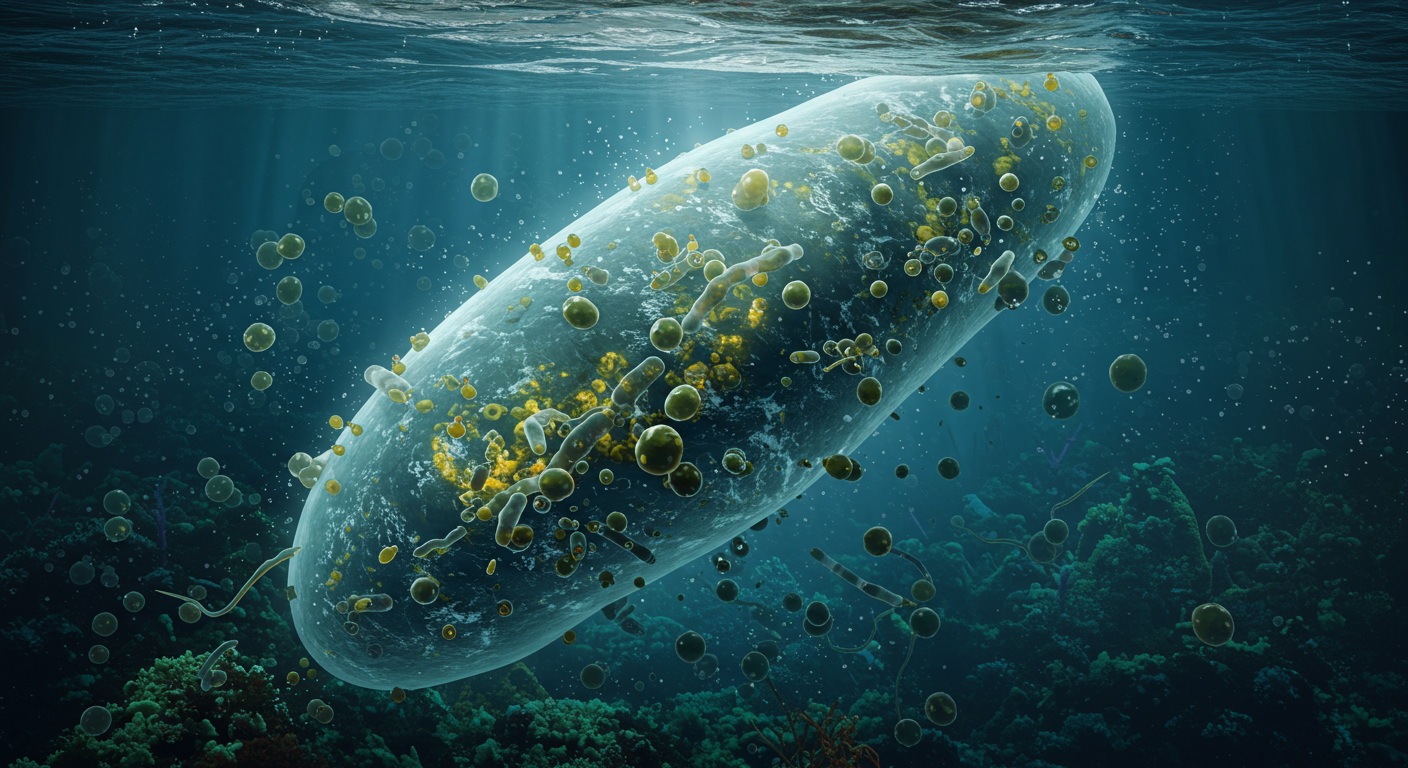

The vast, sunlit surface of the ocean teems with microscopic life, a diverse and unseen world of bacteria and single-celled organisms that form the base of the marine food web. For decades, scientists have understood that these microbes collectively play a role in the Earth’s carbon cycle. However, recent discoveries are revealing that specific, often-overlooked groups of these tiny organisms have an outsized and surprisingly complex influence on how carbon is captured, consumed, and sequestered in the deep sea, prompting a significant reassessment of their importance in regulating the global climate.

These findings are shifting the scientific understanding of marine biogeochemistry from a generalized model to one that acknowledges the specialized and highly efficient functions of a few key microbial players. From bacteria that dominate the ocean through sheer simplicity to ravenous protists that intercept carbon in the ocean’s twilight zone, researchers are discovering that the fate of atmospheric carbon dioxide is intimately tied to the life and death of these microscopic powerhouses. Their actions not only influence the balance of gases in our atmosphere but also regulate the fundamental chemistry of the ocean itself, with profound implications for the future of Earth’s climate systems.

The Simplest Success Story

In the competitive, nutrient-poor environment of the open ocean, one group of bacteria, known as SAR11, has achieved global dominance through sheer numbers. There can be as many as 500,000 of these cells in a single milliliter of seawater. The combined weight of SAR11 bacteria in the world’s oceans exceeds that of all fish. Researchers at Oregon State University have determined that the key to their success lies in their extreme efficiency, a trait encoded in their remarkably compact genome. With only 1.3 million base pairs, it is the smallest genome ever discovered in a free-living organism and contains almost no “junk” DNA, meaning nearly every part of its genetic code serves a vital function.

This genetic streamlining allows SAR11 to thrive and replicate with minimal resources, consuming dissolved organic matter that other organisms cannot efficiently use. Through their immense collective metabolism, SAR11 plays a critical role in recycling organic carbon near the ocean surface. This process releases the essential nutrients that photosynthetic algae need to grow. Since these algae produce about half of the Earth’s oxygen and form the base of the marine food web, the recycling activity of SAR11 is fundamental to the entire ocean ecosystem and, by extension, the global carbon cycle. Their abundance and activity are a major factor in the ocean’s capacity to process organic carbon, which nearly equals the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

A Single Species Dominates Consumption

While SAR11’s success is in its numbers, other research shows that specific microbial species can have an unexpectedly large impact on their own. Scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography investigated the complex mixture of molecules known as dissolved organic carbon, which is released by photosynthetic phytoplankton. This material represents a significant food source for marine bacteria, and its consumption is a key step in the carbon cycle. The prevailing assumption was that a diverse community of different bacteria would be required to break down this varied buffet of molecules.

However, the Scripps researchers found that a single bacterium, *Alteromonas*, was capable of consuming as much of this dissolved organic carbon as a mixed community of many different microbes. This surprising result suggests that individual, highly-efficient species can pull more weight in carbon cycling than previously believed. These “recycling” bacteria are crucial in determining how much carbon is stored in the ocean versus how much is returned to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide when the bacteria respire. Identifying dominant players like *Alteromonas* helps clarify the microscopic mechanisms that govern the ocean’s role as a massive carbon reservoir and provides a more detailed picture of who is responsible for processing this critical energy source.

Intercepting Carbon in the Twilight Zone

The “biological carbon pump” is a crucial process for long-term carbon storage, where dead organisms and waste particles sink from the surface into the deep ocean. This falling organic matter carries carbon with it, and once it reaches the seabed, that carbon can be locked away from the atmosphere for millennia. However, research from Florida State University has revealed that this process is not as straightforward as once thought. Scientists studying the ocean’s “twilight zone,” an area between 100 and 1,000 meters deep, discovered that swarms of single-celled organisms called phaeodarians are intercepting a significant portion of this sinking carbon.

These ravenous microbes consume the carbon-rich particles before they can reach the deep ocean floor. In the limited area studied, scientists found that just one family of phaeodarians was responsible for consuming 20 percent of the sinking carbon particles. This finding has major implications, suggesting that microorganisms around the world could be playing a much larger role in disrupting the carbon pump than previously accounted for in climate models. By consuming these particles in the mid-ocean, phaeodarians effectively divert carbon that would have been sequestered, making it available to the mid-ocean ecosystem but preventing its long-term storage, a distinction that alters calculations of the ocean’s carbon sequestration capacity.

Microscopic Architects of Ocean Chemistry

Beyond bacteria and particle-eating protists, another group of tiny organisms actively shapes the ocean’s carbon cycle through construction. Calcifying plankton, such as coccolithophores and foraminifers, build intricate, microscopic shells out of calcium carbonate, the same material found in chalk and coral. This process of calcification has a profound effect on ocean chemistry and the global climate. As these organisms build their shells, they draw carbon from the surrounding seawater, incorporating it into their solid structures.

When these organisms die, their shells sink. A portion of this calcium carbonate settles on the seabed, forming vast deposits and effectively locking carbon away in marine sediments for centuries or longer. This action is a vital part of the biological carbon pump, directly removing carbon from the upper ocean and, by extension, the atmosphere. The sheer abundance of these calcifying microbes means their collective activity regulates the chemistry of the ocean and plays a significant role in stabilizing the global climate, a service they have been providing for millions of years. Understanding the future health and abundance of these organisms is critical, as about 30% of human-emitted carbon is sequestered by the ocean, and these tiny architects are a key part of that process.

A New Understanding of Carbon Cycling

The accumulation of these discoveries points to a necessary paradigm shift in how scientists view the ocean’s role in the carbon cycle. A recent study from Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, using a novel method to measure microbial activity, suggests that a very small fraction of marine microorganisms is responsible for most of the oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide release in the ocean. This finding challenges the traditional approach of averaging respiration rates across the entire microbial community, which may have obscured the outsized impact of these hyperactive few.

If these foundational ocean processes are indeed dominated by a small number of highly efficient microbes, it has significant implications for the accuracy of climate models. The health, population dynamics, and environmental sensitivities of these key species—whether SAR11, *Alteromonas*, phaeodarians, or coccolithophores—become critically important variables in predicting how the ocean will respond to ongoing climate change. Scientists now face the challenge of identifying these key players across different ocean regions and understanding the complex ecological factors that allow them to dominate carbon cycling. This deeper knowledge is essential for refining global climate projections and for truly grasping the power of the unseen microbial world in shaping our planet’s future.