Astronomers have detected the chemical signature of water vapor being released from 3I/ATLAS, the third interstellar object ever discovered passing through our solar system. The finding is significant not only for confirming the presence of water on a visitor from another star system but also because the activity was observed at an unexpectedly vast distance from the Sun, challenging long-held ideas about how comets behave in the cold, outer reaches of space.

Using the ultraviolet capabilities of NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, a team of physicists from Auburn University identified faint emissions from hydroxyl, a chemical fragment of water molecules broken apart by sunlight. The observations indicate that 3I/ATLAS was shedding water at a rate of approximately 40 kilograms per second while it was nearly three times as far from the Sun as Earth is. This early and distant activity provides an unprecedented opportunity to study the composition of a comet that formed around a different star, offering new clues about the diversity of planetary systems across the galaxy.

A Visitor from Another Star System

First identified on July 1, 2025, 3I/ATLAS followed in the footsteps of two previous interstellar travelers: 1I/’Oumuamua, a rocky, cigar-shaped object that showed no signs of gas or dust, and 2I/Borisov, a comet that was rich in carbon monoxide. Each visitor has proven to be chemically distinct, suggesting a wide variety of conditions in the planetary systems where they originated. While Borisov behaved much like comets from our own solar system, ‘Oumuamua’s inert nature left its classification ambiguous. 3I/ATLAS now provides a third and crucial data point, demonstrating that water-rich comets are not unique to our cosmic neighborhood.

The discovery of 3I/ATLAS triggered a rapid global observation campaign, with astronomers eager to apply lessons learned from the previous two interstellar objects. Characterizing these visitors early in their approach to the Sun is essential for understanding their composition before solar heating significantly alters their surfaces. The detection of water in this instance is a major breakthrough, as water is the primary component of most comets in our solar system and serves as a fundamental benchmark for comparing their overall activity and chemical makeup.

The Ultraviolet Fingerprint of Water

The confirmation of water on 3I/ATLAS was a technical achievement made possible by observing in wavelengths of light invisible from the ground. The key to the discovery was not detecting water molecules directly, but rather their byproduct, hydroxyl (OH), which glows faintly in ultraviolet light after water vapor is broken apart by solar radiation.

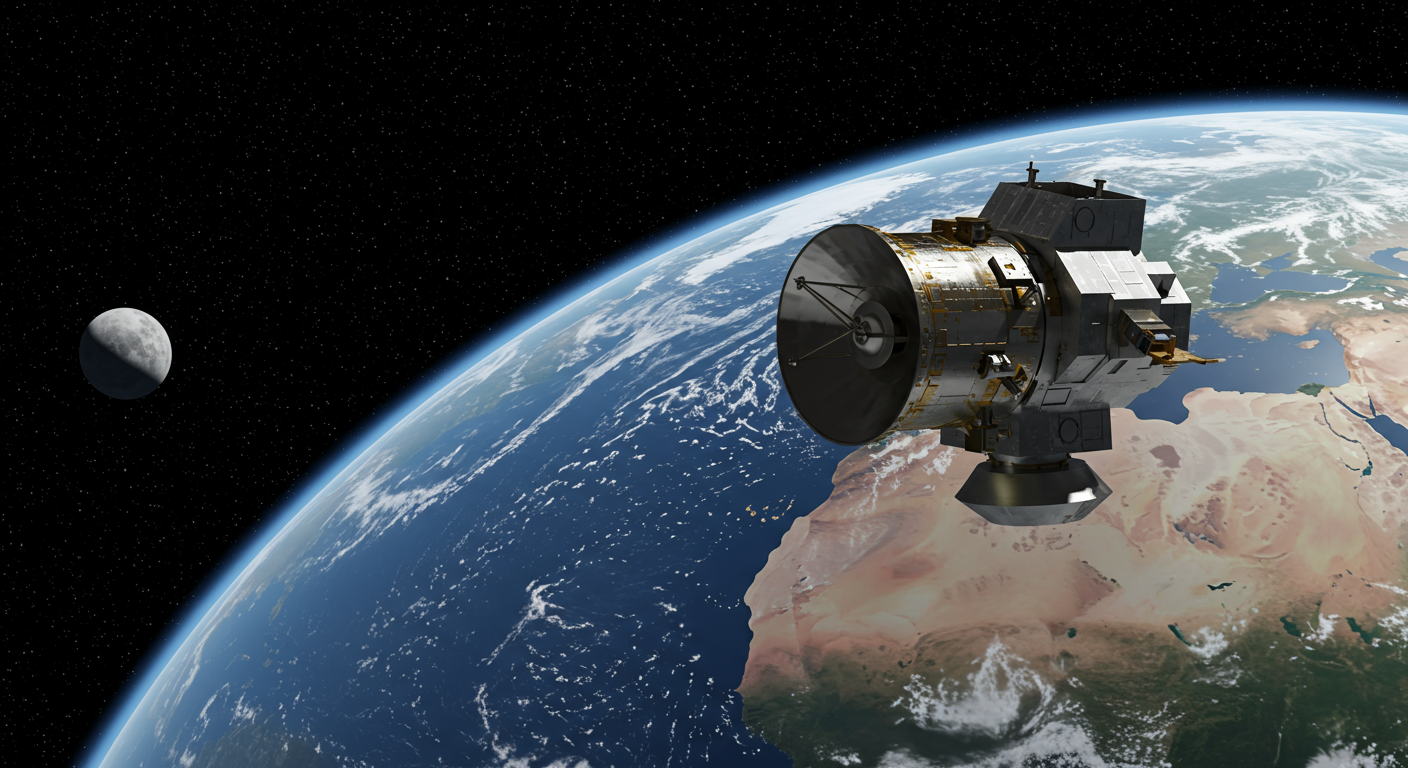

Swift’s Critical Vantage Point

Earth’s atmosphere absorbs most of the ultraviolet light that reaches our planet, making space-based telescopes the only instruments capable of capturing these delicate signals. NASA’s Swift Observatory, though equipped with a modest 30-centimeter telescope, orbits high above the atmosphere, granting it a clear view of the UV spectrum. Its rapid-targeting capability allowed astronomers to point the telescope at 3I/ATLAS within weeks of its discovery, capturing the fleeting hydroxyl signature before the comet moved to a location that was more difficult to observe. The team, led by Auburn University astrophysicist Zexi Xing, took two sets of images, one in late July and another in mid-August 2025, revealing a significant increase in the hydroxyl signal over that period as the comet edged closer to the Sun.

An Unexpectedly Active Comet

The most surprising aspect of the discovery was the comet’s location. 3I/ATLAS was nearly 3 astronomical units from the Sun, or three times the distance between Earth and the Sun, when the observations were made. At this range, sunlight is generally too weak to sublimate water ice directly from a comet’s solid nucleus, a process that typically requires much warmer temperatures. Most comets native to our solar system remain largely inactive and frozen at such distances. Yet 3I/ATLAS was already releasing an estimated 1.36 x 10²⁷ water molecules every second. This high level of distant activity suggests that the comet possesses a mechanism for releasing water that is rare among the comets we have studied so far.

A Novel Mechanism for Water Release

The unusual activity of 3I/ATLAS points to a more complex process than simple surface sublimation. Scientists theorize that instead of ice turning directly into gas on the comet’s nucleus, the object is likely ejecting small, icy grains of dust into the surrounding vacuum. Once detached from the larger body, these tiny grains have a much greater surface area exposed to sunlight, allowing them to heat up and vaporize efficiently even in the cold environment of the outer solar system. This two-step process creates an extended, gassy halo, or coma, around the comet.

This “extended source” phenomenon has been observed in a handful of highly active comets within our own solar system, but its presence in an interstellar visitor provides new insights into cometary physics. It may indicate a complex, layered ice structure within the comet’s nucleus, preserving clues about its formation in a protoplanetary disk around its parent star. This unusual outgassing process helps explain how an object that has spent millions or billions of years in the deep freeze of interstellar space can become active so quickly and so far from a star’s warmth.

Comparing Cosmic Chemistry

The detection of water, a molecule fundamental to life as we know it, allows for the first direct comparison of an interstellar comet’s chemistry with the vast catalog of comets from our own solar system. Water serves as a universal yardstick for measuring cometary activity and composition. “When we detect water—or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH—from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from another planetary system,” said Dennis Bodewits, an astronomer at Auburn University. By analyzing the amount of water and other volatiles, scientists can begin to place 3I/ATLAS on the same chemical scale used for native comets, helping to determine whether the building blocks of planets are similar from one star system to another.

The distinct personalities of the three known interstellar objects highlight the chemical diversity that exists across the galaxy. ‘Oumuamua was dry and rocky, Borisov was carbon-rich, and 3I/ATLAS is remarkably active with water at a great distance. This growing dataset suggests that the materials that form planets can vary significantly, providing a richer understanding of how planetary systems, including our own, come into being.

Future Observations and Unanswered Questions

Although 3I/ATLAS has temporarily faded from view, it is expected to become observable again in mid-November 2025 as its trajectory brings it back into the line of sight of telescopes. Astronomers are eager to continue tracking its activity as it makes its closest approach to the Sun. Continued observations will allow scientists to monitor how its water production changes with temperature and to search for the signatures of other gases locked within its ice.

The data gathered from this rare visitor will be analyzed for years to come, offering a unique window into the chemistry of another star’s planetary nursery. The discovery has underscored the importance of rapid-response observatories like Swift, which can be retasked quickly to study transient celestial events. As more interstellar objects are discovered in the coming years, each one will contribute another piece to the puzzle of how planets and comets form throughout the cosmos.