Astronomers studying the universe’s infancy have detected a faint radio signature from the very first stars, offering a glimpse into a pivotal and previously unobservable era known as the “cosmic dawn.” The signal, originating from a time when the universe was only 180 million years old, suggests that the cosmic environment was far colder than most standard cosmological models had predicted. This unexpected discovery opens a new window into the properties of the earliest stellar bodies and raises profound questions about the nature of dark matter.

The groundbreaking observations hinge on a specific wavelength of radio emission from neutral hydrogen, known as the 21-centimeter line. By capturing a subtle absorption feature in this signal, researchers have found the first observational evidence of the universe’s transition out of a starless “dark age.” The intensity of this feature implies that the primordial hydrogen gas was cooled to temperatures less than half of what was expected, a finding that could point to a previously unknown interaction between normal matter and dark matter and may require a significant revision of astrophysical theories.

Unlocking the Universe’s Dark Ages

Following the Big Bang, the universe entered a period of darkness. For several hundred thousand years, it was a hot, dense soup of particles. As it expanded and cooled, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen atoms, rendering the cosmos transparent to light for the first time. This event released the radiation that we now observe as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), a faint afterglow that permeates all of space. However, this early universe was devoid of stars and galaxies, a period cosmologists refer to as the cosmic dark ages.

This era ended with the gravitational collapse of dense regions of gas to form the very first stars. The period during which these first stars ignited and began to illuminate the cosmos is called the cosmic dawn. Direct observation of these pioneering stars, known as Population III stars, is beyond the capability of even the most powerful modern telescopes. Instead, astronomers search for the indirect effects these stars had on the vast clouds of neutral hydrogen that surrounded them. The faint radio waves emitted by this hydrogen, known as the 21-centimeter signal, provide a unique probe of this ancient epoch.

Capturing a Whisper from the Past

Detecting the 21-centimeter signal from the cosmic dawn is an immense technical challenge. The signal is incredibly faint and is drowned out by radio noise from our own galaxy and from human-made sources on Earth, which can be thousands or even millions of times stronger. To overcome this, researchers build observatories in the most remote, radio-quiet locations on the planet.

The EDGES Experiment

The first successful detection was reported by a team using the Experiment to Detect Global EoR Signature (EDGES), a small radio antenna located in the Western Australian desert. The EDGES team observed a distinct dip in the radio spectrum, consistent with the absorption of CMB radiation by neutral hydrogen as the first stars switched on. The frequency of this absorption profile indicated that this momentous event occurred approximately 180 million years after the Big Bang. This finding provides the first concrete timeline for the end of the cosmic dark ages.

Next-Generation Observatories

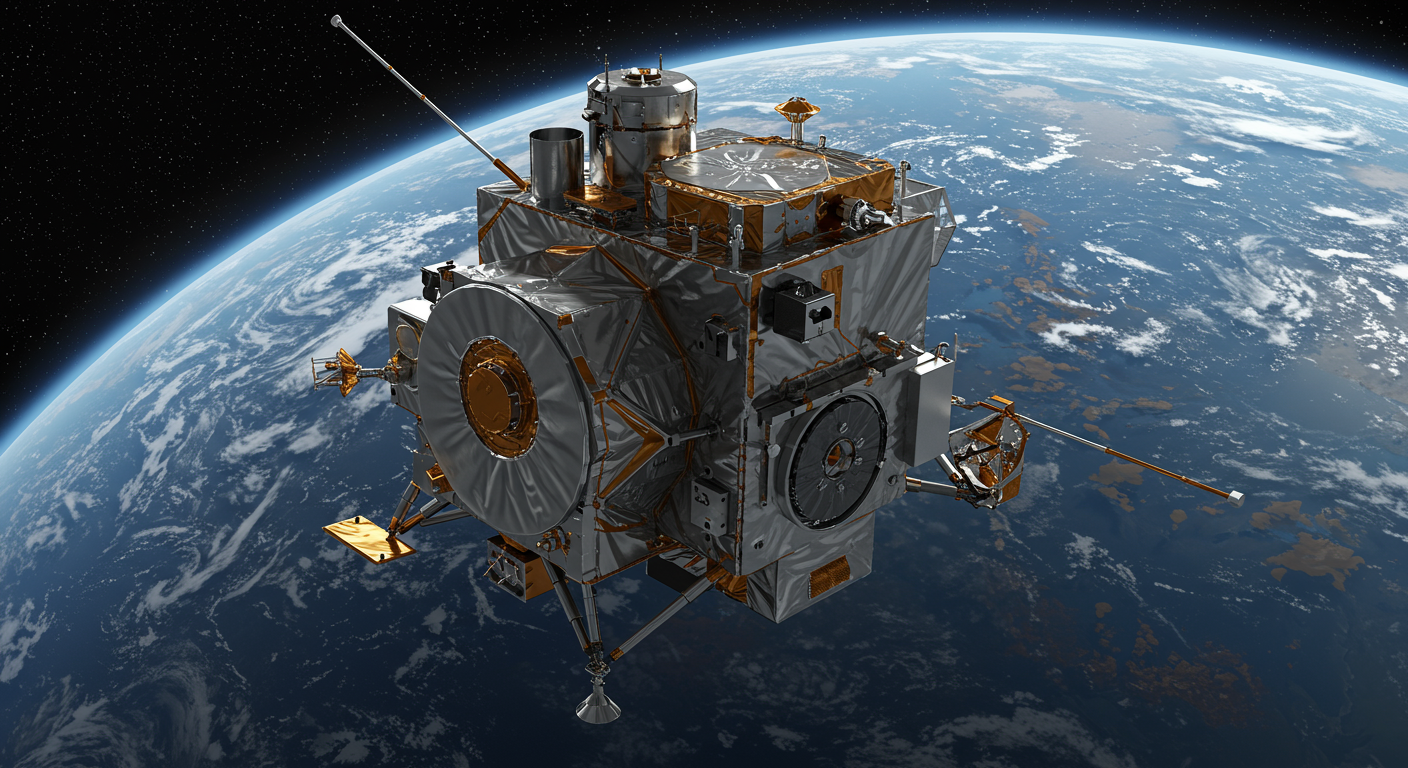

While revolutionary, the EDGES detection is a single data point, and the scientific community awaits independent confirmation. Several other projects are poised to contribute. The Radio Experiment for the Analysis of Cosmic Hydrogen (REACH) is a similar experiment designed to verify the EDGES result with higher precision. On a much larger scale, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), a massive international radio telescope project under construction in Australia and South Africa, will eventually be able to map the 21-centimeter signal in three dimensions across vast areas of the sky. These powerful new instruments promise to move beyond a simple detection to creating detailed maps of how the universe lit up.

A Surprisingly Frigid Beginning

The most startling aspect of the EDGES result was not the timing of the cosmic dawn, but the temperature it implied. The absorption feature detected was more than twice as strong as the most optimistic theoretical predictions. According to cosmological models, the strength of the absorption dip is directly related to the temperature difference between the hydrogen gas and the background radiation. A stronger dip means the hydrogen gas was significantly colder than anticipated.

Standard models of cosmic evolution predicted a minimum gas temperature of around 10 Kelvin. The EDGES data, however, suggests the gas may have been as cold as 5 Kelvin, or even lower. This profound discrepancy points to a missing piece in our understanding of early universe physics. It suggests that some unknown mechanism was actively drawing heat out of the primordial hydrogen gas long before the first stars had a chance to heat it back up.

A Potential Clue to Dark Matter

One of the most exciting, though still speculative, explanations for this unexpected cold is a potential interaction between ordinary matter and dark matter. Dark matter is the mysterious, invisible substance that is believed to make up about 85% of the matter in the universe. Its existence is inferred from its gravitational effects on galaxies and galaxy clusters, but its fundamental nature remains one of the biggest puzzles in science.

The standard model of cosmology assumes that dark matter interacts with ordinary matter only through gravity. However, if the hydrogen gas of the early universe was able to transfer some of its heat to the much colder dark matter through some form of non-gravitational interaction, it would explain the observed discrepancy. If this hypothesis is confirmed, it would not only solve the puzzle of the unexpectedly cold gas but would also provide the first direct evidence of a fundamental interaction between dark matter and the world of familiar particles, opening a new frontier in physics.

The Future of Cosmic Dawn Research

The detection of a signal from the cosmic dawn has inaugurated a new era of observational cosmology. The immediate next step is for other experiments, such as REACH, to confirm the EDGES finding. Subsequent observations with more powerful instruments like the SKA will be crucial for ruling out instrumental effects and for mapping the signal in detail. As stated by Professor Anastasia Fialkov of the University of Cambridge, a key researcher in this field, this is a unique opportunity to learn how the universe’s first light emerged from the darkness. The coming years promise a flood of new data that will test these initial, tantalizing results.

These faint radio signals carry enormous potential for discovery. They could help determine the mass and properties of the first stars, reveal the timeline of the Epoch of Reionization—when the light from the first galaxies reionized the neutral hydrogen—and potentially, unlock the secrets of dark matter. The transition from a cold, dark universe to one filled with stars is a story that astronomers are only now beginning to read.